Common Sense Water-Conservation (CSWC)

The Issue

What You Need to Know About Water Scarcity

You might not know it, but the U.S. relies on a myriad of 204 basins (fresh water deposits) for everything from agriculture, to industry and personal use. Of those 204 basins, 96 are expecting significant shortages by 2050 (Heggie, 2020, para. 2) and of those 96, 83 (the source of more than 40 states current water supplies) could start running dry as early as next year (Heggie, 2020, para. 3). Historically, these basins are fed water from snowcap runoffs and rainwater (USGS, 2005, para. 2), elements of the atmosphere undergoing massive regional transitions as a result of climate change (IPCC, 2019, Ch.4.3.2.1, para. 1)

In normal conditions the Earth's underground freshwater aquifers acts as a sort of natural fail-safe, providing people access to ancient freshwater deposits which have filled up over millennia. However as of late, the aquifers in the U.S., and around the world have been pumped to a point of relative exhaustion (Griggs, Miller & Sanderson, 2020, para. 3, 5; Goergin, 2019, para. 3), often for commercial benefit; and the process of refilling these liquid saving accounts takes thousands of years.

This, in addition to severe droughts and heat waves associated to climate change, is creating a dire situation that demands immediate, drastic action if we hope to pass on the most essential element of life to future generations.

WaterFlowsFoodGrows.jpg |  FolsomLake2011.png |  Folsomlake2014.png |

|---|---|---|

Colorado River Depletion |  Dry Riverbed |

Despite photos like those shown above, as well as a myriad of very real, documented potential for global water stores being depleted in the near future, little to no legislative or social action has been taken in response. The reality is either too daunting for most to want to wrestle with or is overlooked entirely as nations across the globe continue to frivolously waste trillions of gallons of water on outdated practices in fields like agriculture and energy production.

In the U.S. alone, agricultural water consumption, which constitutes nearly 90% of all groundwater withdrawals in the nation, is estimated to be about 34 trillion gallons annually (Hrozencik, 2019). A staggering number that is only bound to increase as the demand for animal products - which rely largely on the consumption of soy, corn and oats - is expected to increase by an astounding 58% by 2030 (WHO, 2008).

From west to east, water scarcity is an issue that continues to envelope the modern world. In regions ranging from the central plains of the United States, to the valleys of Mexico and Chile, and the shores of Syria, Africa and the whole of Asia, water is becoming increasingly hard to come by (Alexander, 2019, para. 16; Ayala, 2020, para. 1&7; Gallagher, 2016, para. 1; Goering, 2019, para. 3, 8, 10; Leung, 2020, para. 3; Mwenda & Simoncelli, 2020; Olivieria, 2020, para. 7).

Subsequently, populations abroad are facing acute and chronic environmental consequences as attempts to sustain the status quo rivals the need to make substantial change. As the world inches closer to 'watergeddon' the need to regulate and improve existing practices is higher now than ever before. If something is not done soon to not only conserve existing supplies, but prevent future misappropriation of water sources, you could one day find yourself in a position where the faucets run dry.

Need proof? Below you will find but a few examples of the catalysts ramping up the encroaching water crisis.

Thirsty Industries

Exploring the Avocado Trade

While presenting a great boon to both North and South American economies, the explosion of the fruit's popularity has also exacerbated existing water scarcity issues in regions that specialize in avocado cultivation. This exacerbation often manifests because the potential to make large profits creates an incentive for institutions / corporations to greatly deplete freshwater sources (through both legal and illegal avenues) to satiate the thirsty industry.

In Chile, for instance plantation owners were found to have been illegally "depriving local villages" of access to already scarce water supplies by "diverting [water sources like rivers]" (Mwenda & Simoncelli, 2020) into irrigation canals to meet annual production quotas. This has lead to a state where "millions of people are regularly left without running water for days at a time" (Gallagher, 2016, para. 1&3) so corporate entities can make a profit.

This issue is not isolated to Chile, but is one which Mexico is facing in some degree as well as extreme water shortages have begun to manifest as a consequence of rapid urbanization and a growing global demand for avocados; each of which prompts excessive depletion of local aquifers and above ground water sources (Ayala, 2020, para. 1&7; Olivieri, 2020, para. 7).

While thirsty crops like avocados are certainly a cause for concern from a standpoint of water conservation, when it comes to water depletion globally, the fatty fruit is responsible for a relatively small withdrawal. As of 2018, the USDA estimated Mexican avocado production to be 1.9 million metric tones (USDA, 2018). Given that it requires 32 gallons of water to produce 1 pound of avocados in Mexico (Kruskal, 2016, para. 10) this means that as of 2018 (assuming growing conditions have maintained from their 2016 levels) the Mexican avocado industry required approximately one hundred thirty four billion, thirty nine million, six hundred eighty thousand (134,039,680,000) gallons of water to satisfy avocado production quotas. A seemingly staggering quantity that you may be surprised to hear actually pales in comparison to the water needed to grow the worlds most popular commodity crops.

The Great American Grain Elevator

Exploring the West's Production Treadmill

Driving through the American West you've likely seen the iconic fields of corn, wheat and soybeans often huddled together so tightly it's hard to see the rows between them. Indeed, vast majorities of the nation's land have been dedicated to growing commodity crops (Leatherby & Merrill, 2018, para. 6-9). The reasoning behind which farmers do so has been linked largely to the fact that "the industrial commodity system--buys only corn and soybeans [and] it's near impossible...[for farmers] to sell anything else" (Bittman, 2019, para. 5).

The impacts of this business model has taken its toll on places like Iowa in particular. Lands that were once filled with prairie and wetlands as far as the eye can see are nearly unrecognizable from what they were not 200 years ago. And in this seemingly endless array of "neatly partitioned grids of intensively cultivated land" lay the "model for the farm as factory" (Bittman, 2019, para. 3). As of 2019, 90% of all land in the state is dedicated to farming, 63% of which are dedicated solely to corn and soybeans (Iowa's Most Popular Crop, 2020; Bittman, 2019, para. 4).

For reference, Iowa has an area of approximately 36 million acres. Assuming half of the 63% mentioned above is for corn and half is for soybeans, one can assume that 31.5% or 11,340,000 acres of Iowa land is dedicated solely to growing corn; though actual amount are likely higher as corn is estimated to be the state's dominant crop.

Taking this area into consideration with the fact that it requires nearly "600,000 gallons of [total] water" to cultivate an acre of corn (USDA-ARS, 2011), that would mean Iowa's cornfields require (from a conservative estimate) more than 6 trillion gallons of water each year to sustain current output. That is more than 50x the annual water consumption needed to produce Mexico's avocados; and that is only a fraction of one state's commodity crop production. In fact its arguably safe to assume that corn and other commodity crops are the biggest culprits to date when it comes to frivolous water consumption practices.

Granted rainwater will no doubt supply substantial portions of the total water needed to satiate Iowa's cornfields, as climate change continues to change our world, we cannot rely on the blind hope and optimism that rainfall in the region will sustain indefinitely. Issues of the like are familiar to farmers of the area who between 1900 and 2008 extracted nearly "89 trillion gallons" from the Ogallala-High Plains Aquifer to satisfy demands for water that were not met by rainfall (Griggs, Miller & Sanderson, 2020, para. 3). In states like Kansas (another state dominated by commodity crop production), day zero - "the day wells run dry - has already arrived for about 30% of the aquifer accessible to the state and within 50 years, the entire aquifer is expected to be 70% depleted" (Griggs, Miller & Sanderson, 2020, para. 7).

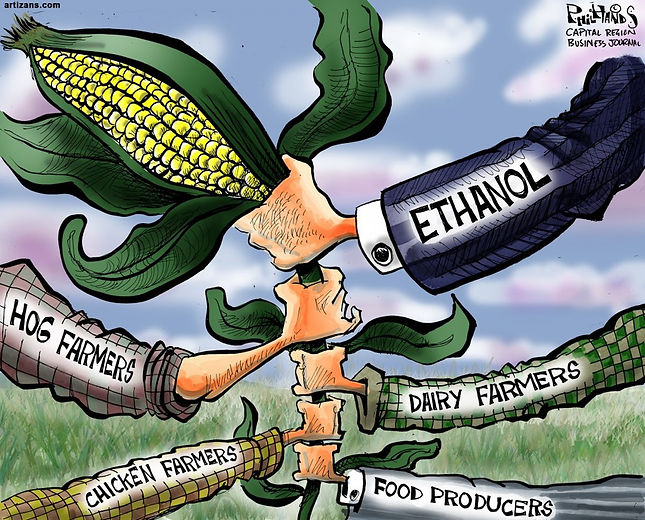

Interestingly, less than 1% of the corn then produced by this industrial system is sweet corn that is edible by humans. Up to 50% is used to produce ethanol, and the rest, much like their soybean counterparts, go to feed animals in confinement (Bittman, 2019, para. 7).